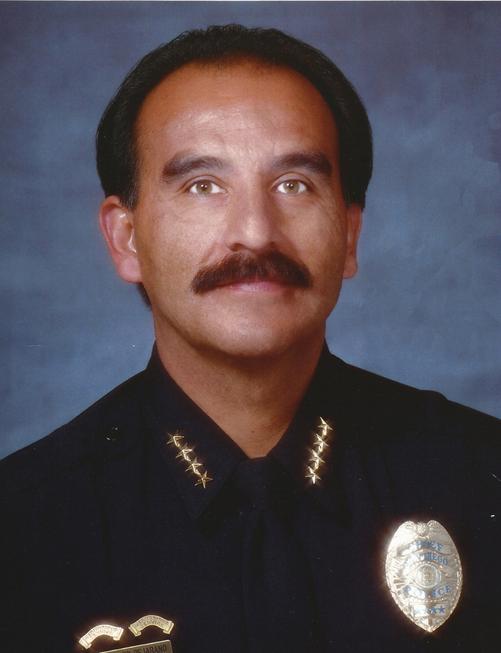

CHIEF RAUL D. "DAVID" BEJARANO

05/27/1999 - 04/15/2003

When David Bejarano graduated the San Diego police academy in the summer of 1979 he already had a career goal in mind - make detective sergeant in 20 years. That being the case, the 42-year-old former Marine must have been very pleased to find on his 20th anniversary, he was chief of police.

Working his way through the ranks as a patrol officer, detective and supervisor, Bejarano had a well-rounded career and was well regarded.

When asked by the media about his Hispanic background shortly after his appointment as chief, Bejarano replied, “Obviously I'm very proud of my heritage, but I've tried not to focus on being Latino. I'm the chief for the entire city.” Despite Bejarano's willingness to embrace everyone in the city, the April 26, 1999, appointment of San Diego's first Hispanic police chief since Antonio Gonzales was not without controversy.

At his confirmation hearing, another candidate for the job, Assistant Chief Rulette Armstead, raised a question of fairness when she claimed City Manager Mike Uberuaga had not conducted the interviews in an equitable manner.

A further claim was made that Mayor Susan Golding had interfered with the hiring process by interviewing not only her, but also Assistant Chiefs John Welter, George Saldamando, and LAPD Assistant Chief Mark Kroeker. If the claim was true, and Golding was acting in an official capacity as mayor, it would be a violation of the San Diego Municipal Code and she would be guilty of a crime.

Several members of the San Diego Black Police Officer's Association attended the hearings and backed Armstead's claim. To ensure the selection process was done without bias, Armstead and several members of the BPOA, demanded a delay in the hearing until the allegation could be investigated.

City Attorney Casey Gwinn responded by addressing the council and assuring them there was no violation of the law. Golding's response was she was simply doing what any private citizen was entitled to do when they had a vested interest in public safety. She had interviewed the candidates only for personal reasons and was not attempting to influence the managers' decision.

In the end, the council voted 7-0 to confirm Bejarano as the 34th Chief of Police. He would quickly discover, like a number of chiefs before him, the honeymoon period would be a very short one when a simple misunderstanding created a firestorm.

The controversy began when the San Diego Union-Tribune reported on July 28, 1999, the police department was considering a policy change in the way burglary investigations were being handled. Considering only 9-13% of residential burglaries are ever solved, Bejarano asked his staff to look into more efficient ways to handle the issue. Was there a way to do something that wasn't being done already that would free up a police officer to focus on other issues such as prevention? By the time it filtered out to the media though, Bejarano found his words twisted to the point of saying police officers would no longer investigate burglaries unless there was either a suspect in custody or a preponderance of evidence pointing directly to one.

Mayor Golding read about the "new policy" in the newspaper and was outraged. She quickly called the chief and demanded to know why neither she, nor the council, was made aware of such a dramatic change in philosophy. Golding wasn't the only one upset either. The chief's office and even City Hall found themselves facing the public's wrath in the form of angry phone calls and e-mail.

In response to the communities concerns, Bejarano made a public statement directly addressing the issue. He stated something certainly needed to be done with the 9-13% solvability rate but added, "I am not comfortable with any course of action that undermines the public's confidence in this department to investigate crime. As a result, we have not changed how we do business and I do not anticipate us doing so." The firestorm was over as quickly as it had begun.

One year after taking office Bejarano would sit back and reflect how quickly time had passed. He recalled the most harrowing moment of being chief was when he held the hand of critically injured Mitch Vitug after he had been shot. “There was a lot of emotion. I saw him as a member of my family. I told him he was going to be OK, to hang in there, that his father was on the way and he was in good hands.”

In perhaps the most poignant statement, Bejarano commented, “I was surprised at how quickly the year went by. The job is a lot more high-profile than I thought it was going to be.”

In the year 2000, Bejarano was faced with a potentially explosive issue when racial profiling came to the national forefront. The issue wasn't exactly new. Since the beginning of American policing, complaints have existed that some officers enforce the law differently when it comes to minorities than when it comes to whites.

Essentially complaining police officers across the US unfairly target minority motorists, many civil rights groups demanded full-scale investigations into why police officers make traffic stops on some citizens and not others. As the issue grew across the country, many police departments responded to the complaints by simply doing nothing. Choosing to be proactive, Bejarano issued a department order stating for a six-month period, all patrol and traffic officers would record the race of every motorist stopped and the reason they were detained. At the end of the study the numbers would be analyzed to determine whether or not the complaints were valid or based more upon perception.

At the end of six months the data was analyzed and it was found SDPD officers do in fact stop minorities at a higher rate than their representation (according to the census) within the community. Bejarano released the study results to his officers at the same time he met with the press to explain what the numbers meant. Bejarano told the press because of San Diego's proximity to the US/Mexico border and its large military population, it couldn't be accurately determined what percentage Blacks and Hispanics really occupied in the San Diego population. Another factor was on all California driver's licenses there is not a section for race. Without this information it was almost impossible to determine if San Diego police officers were really engaged in racial profiling.

In light of the information, Bejarano vowed to continue the study and also to closely monitor officers to determine if officers were engaged in the practice. Bejarano made it known, both through messages to his officers and to the public, that officers would continue to do aggressive but fair law enforcement and disparaging treatment of any group would not be tolerated.

In early 2003 Bejarano announced President George W. Bush was considering him for the position of the United States Marshal for the Southern District. In May 2003 he officially resigned as chief of police when the nomination became official. His departure left Executive Assistant Chief John Welter as the interim chief while city manager Michael Uberuaga conducted a national search for the department’s next leader.

David Bejarano stepped back into local law enforcement in 2009 when he was appointed as the chief of police for the Chula Vista Police Department.