Philip Crosthwaite was born to American parents in Ireland on December 27, 1825.

At age 20 he was visiting Rhode Island when he and a friend hopped a schooner for what they thought would be a short fishing trip. Shortly after leaving port the trip turned into a more serious matter. The boys discovered they had been tricked and the true destination was San Francisco.

On October 16, 1845, after several months at sea, the ship pulled into San Diego harbor for a supply stop. Under the cover of darkness, the boys snuck off the ship and into town.

Being young boys in a strange place isn’t easy and within a short period of time they began to get homesick.

After discovering the only eastbound ship in port had just one available berth, the friends tossed a coin for the space. Phillip lost the coin toss and remained on the west coast for the rest of his life.

The 1850 census listed Philip Crosthwaite as Fillipe Cruz and his occupation as a laborer. In that same year he challenged Agoston Haraszathy for the office of City Marshal. Despite losing the election, he managed to become the first County Treasurer when Juan Bandini declined the position. In his first year the politically ambitious man quickly discovered the job to be quite profitable.

At the time he took office, state law required each Treasurer to appear in person in Sacramento once a year and pay any money due the state. When Philip went north to hand in $200.00 that was due for the county, he traveled on a steam ship in the finest cabin and ate the best food. Ironically, his travel fees amounted to $300 so he wound up returning with more money than he took. After seeing his expense report, the State Controller suggested under similar conditions it would be better if he simply embezzled the public money.

In November 1851 Jonathan Warner reported raids on his backcountry ranch bringing Phillip into the war between the city and the Indians. A volunteer company was formed to put down the uprising with Crosthwaite appointed as a sergeant. He quickly discovered outsiders were a bigger problem than the rebellious Indians.

When the war broke out San Diegan's appealed to Governor McDougall’s office for help. Answering the call was a San Francisco gang by the name of “The Hounds.” The uprising was actually put down before the Hounds left. The gang knew this but set sail anyway. When the Hounds arrived they were greeted hospitably and allowed to set up camp in Mission Valley. It didn’t take long for rumors to start among the residents that the Hounds were stealing horses for an unknown expedition.

On December 31, 1851, several Volunteers left over from the war attended a dance in Old Town. Around midnight Cave Couts told Philip some of the Hounds had come into town to steal more horses. Couts ordered Philip to take some men and arrest any Hound they could find. Before long, the posse caught a man with a mule that belonged to Juan Bandini. After questioning the man the Volunteers discovered Isaac Van Ness was their leader and he had made plans to take the animals’ south to Baja California.

Phillip had one of his men guard the prisoner as he led other men to hunt down the rest of the gang. At the edge of the San Diego River they found Van Ness and another Hound named Sergeant Thomas. Wanting to catch the rest of the group, the Volunteers did not arrest Van Ness, but decided to lock Sergeant Thomas up in the courthouse.

As Phillip and his men escorted Sergeant Thomas back to town they met a captain of the gang who asked why his men had been arrested. When Philip told him of Couts orders, the captain demanded the Volunteers turn his men loose. Philip refused, instead taking Sergeant Thomas to the courthouse where he was locked up. The next day the captain went to the courthouse and again demanded the release of his man and once more Philip refused. As the captain left he yelled he was going to get the rest of the Hounds to come back and take over the town.

Fearing an all out war, Philip started looking for reinforcements and quickly discovered there was a company of infantry soldiers camped several miles from Old Town. Preparing for the worst, he rode to the camp and asked for the soldiers’ help. Knowing what was at stake, the company commander, Lieutenant Sweeny, rounded up a sergeant and eighteen soldiers to assist back in town. As the soldiers gathered their gear back at the camp, Philip rode back to Old Town to begin to make plans for the Hounds return.

When the soldiers arrived in town they found Phillip and Judge James W. Robinson in the plaza making arrangements for a trial of Sergeant Thomas. Realizing war could break out at any time, Lieutenant Sweeny placed his men in a building at the edge of the square and walked alone into the plaza.

Lieutenant Watkins of the Hounds approached Philip and asked if he was the one who arrested his men. As soon as he answered “yes”, Watkins threw a punch but Philip managed to dodge the blow. Watkins then pulled a pistol, aimed it directly at Philip and pulled the trigger. Fortunately the gun didn’t fire and Philip was able to get his own gun out and shoot Watkins in the leg. The fighting between the two men caused the rest of the Hounds to open fire from various points in the plaza. One of the shots struck Philip in the hip but he managed to continue shooting until his gun jammed.

Seeing the shooting, Doctor Ogden ran into the plaza, picked up Philip and carried him into a store. As the Hounds chased Dr. Ogden, Lieutenant Sweeny signaled his men. With guns blazing, the soldiers charged the plaza and drove the gang back.

Because of his wounds, Lieutenant Watkins’ right leg had to be amputated. Philip was much more fortunate and fully recovered. The January 24, 1852, San Diego Herald reported, “Phillip Crosthwaite has so far recovered as to be considered out of danger.” The Hounds, meanwhile, had returned to San Francisco on another chartered ship. With the Hounds gone, life returned to normal and the Volunteers were disbanded.

Phillip Crosthwaite would hold a number of county offices before the Board of Trustees appointed him City Marshal in September 1869. With a salary of $60 per month payable in gold, he would be responsible for keeping the peace in the town but history books show him running a general store with Thomas Whaley.

He served as San Diego’s top lawman until August 1872.

THE THIN BLUE LINE

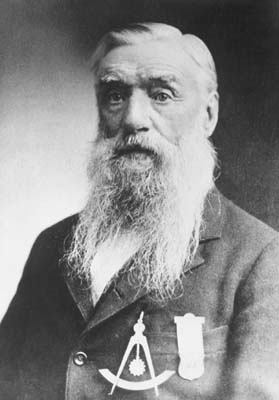

CITY MARSHAL PHILIP CROSTHWAITE

SDCMO 1869 - 1872

12/27/1825 - 02/19/1903

Basic information is provided as a courtesy and is obtained from a variety of sources including public data, museum files and or other mediums. While the San Diego Police Historical Association strives for accuracy, there can be issues beyond our control which renders us unable to attest to the veracity of what is presented. More specific information may be available if research is conducted. Research is done at a cost of $50 per hour with no assurances of the outcome. For additional info please contact us.