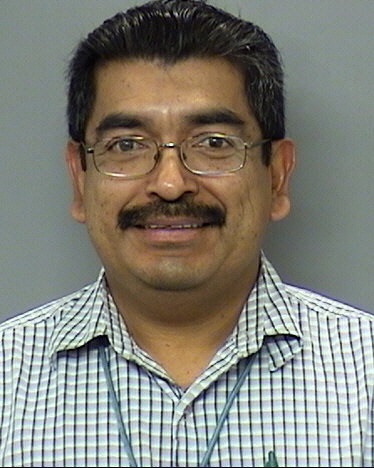

POLICE CHAPLAIN HENRY RODRIGUEZ

SDPD 05/24/2000 - 08/04/2016

03/25/1955 - 08/24/2016

THE THIN BLUE LINE

Rev. Henry Rodriguez Jr., 1955-2016: An advocate for community, police

By Peter Rowe

Late on July 28, the Rev. Henry Rodriguez left his sick bed and hurried to a crime scene. Then he drove to Mercy Hospital.

Although he was suffering from pneumonia, Rodriguez wasn’t there for his health. He was there as a San Diego Police Department chaplain, comforting the family of slain Officer Jonathan De Guzman.

“He was in the hospital room with Officer De Guzman,” said Sgt. Edward Zwibel, one of Rodriguez’s closest friends, “attending to the needs of others even though he was very ill.”

Rodriguez, 61, died Aug. 4 — the same day as De Guzman’s funeral Mass, a service the Roman Catholic priest had planned to attend before his condition worsened. When news of his death spread through the church, the police officers absorbed yet another blow.

“There was an audible sigh,” Zwibel said. “It was like you’re kidding.”

A San Diego native, Rodriguez occupied a unique position. The long-time pastor at St. Jude Shrine of the West, he also served as a chaplain to the police, Scripps Mercy Hospital and San Diego Hospice. While he had powerful friends — a marathoner, Rodriguez often ran with former City Manager Jack McGrory — he relentlessly advocated for the powerless, sometimes irritating bishops, mayors and police chiefs.

Yet friends and colleagues insist he built more bridges than he burned.

“He was dedicated to the community and to the police,” said former Police Chief Jerry Sanders, who met Rodriguez in 1988. “That was kind of a strange juncture at the time, but he was able to carry that off like no one else.”

Coming home

Henry Rodriguez Jr. was born March 25, 1955, at Paradise Valley Hospital. The second of six children, he was always interested in religion. As a boy, he built an altar in his bedroom. A sister, Linda Rodriguez, remembers him conducting a funeral for a dead bird that had been found near the family’s Southcrest house.

The family attended Sunday Mass at St. Jude, where Henry served as an altar boy. Jennie Rodriguez remembers her son as a good boy, smart and kind. But he had a difficult adolescence and dropped out of Memorial Junior High School.

Henry spent a few years on the streets — as a priest, he once told a friend that he was approaching the same dead end as the gang members he counseled — before volunteering at Sharp Memorial Hospital.

“You help out the nurses, lift patients, take them up to the X-ray department,” said Steve Best, who met Rodriguez in 1973, when both were orderlies. “Henry basically grew up at Sharp. He liked it and was really good at it.”

Nurses encouraged the young orderly to get an GED. When he did, they helped pay his college expenses. In 1981, he graduated from University of San Diego with a bachelor’s degree in sociology.

He entered St. Francis Seminary, also at USD, and was ordained a priest in 1986. After graduate studies in Minnesota and Rome, he came home to Southcrest.

As associate pastor at St. Jude, he assisted the same priest who had presided over his first communion, the Rev. Ned Brockhaus. Rodriguez also became a leader of the San Diego Organizing Project, protesting plans to push a freeway spur through the surrounding neighborhood.

Around the same time, he invited a young police captain to meet with residents.

“Later, I called those the ‘SDOP Pressure Sessions,’” said Sanders. “They had it all orchestrated, a list of questions, people would line up and just hammer away.”

Somehow, the captain got through the meeting. “Boy,” he recalled, “I was stumbling.”

Afterward, the priest took him aside. “We just need your help,” he said.

Like Sanders, Rodriguez believed in community policing, seeing the cop on the beat as a neighborhood ally. And residents needed allies. The priest’s brother, Vincent, had been murdered in the area in 1987. Parishioners told their new priest that the streets around St. Jude were known for drugs and prostitution.

At protests, some who marched with Rodriguez saw cops as the enemy. He didn’t. In 1989 the priest volunteered as a police department chaplain, a position he would hold to the end of his life.

“He was someone who was very comfortable representing his church, his community and the police department,” said Kevin Malone, executive director of the San Diego Organizing Project, “and holding everybody equally responsible.”

St. Jude’s became a hub of activism — of all sorts. Father Brockhaus was returning from an errand when he saw police cars surrounding the church.

“Is there a problem?” a worried parishioner asked.

“No,” Brockhaus replied. “The officers are just stopping by to see Henry.”

Better ways

Rodriguez ran the Boston Marathon at least three times, and the San Diego Rock ’n’ Roll marathon at least twice. (Personal best: Boston, 2002, 3:27:41.)

He wasn’t always on duty, but he was always on call. He was pastor at St. Jude until 2006, then added hospice duties to his list of ministries. “He really found great meaning in caring for the terminally ill,” said Zwibel.

On July 1, he became pastor of St. John the Evangelist Church in Hillcrest. He welcomed the return to parish life, but the long hours caught up with him. Last month, whooping cough led to pneumonia. Still, he tried to fulfill all his duties.

“He put everything into working with other people,” said former Police Chief William Lansdowne, “and took very little time for himself.”

One reason he worked so hard: He enjoyed people. One Christmas Eve, Rodriguez joined Lansdowne for a ride-along. They came across the woman with two kids standing by a car. They had been pulled over by a patrolman, who cited her for driving without a license — and then called for a tow truck.

“Father Henry looks at me and says, ‘You know, there’s a better way to do this,’” Lansdowne said.

Mother and children were sent their way, with a warning: “You need to take care of this.”

Another night, the chief and the priest responded to a domestic disturbance call in a home near St. Jude. The screaming couple weren’t impressed to see the chief at their door, but then they noticed the other guy.

“Father Henry,” the man said, “I’m so sorry.”

Other calls were more difficult. The police department now has 16 volunteer chaplains. They represent a wide variety of faiths and are called on for a broad range of services. They perform weddings and baptisms, but also conduct funerals. They counsel officers who are beset with troubles, marital and financial.

And they respond when people face death — the deaths of police officers and of family members.

“They really are just great, great friends,” said Zwibel, noting that, while no officers are ever required to see a chaplain, many do. “And Father Henry was like the full coordinator of the program for years.”

Soon after Zwibel joined the department in 1998, his godfather died. At the funeral, Rodriguez offered condolences and something more.

“He offered himself in my godfather’s place,” Zwibel said, “to take on that role.”

Several times, Lansdowne witnessed Rodriguez break tragic news to unsuspecting family members. “He taught me that you have to get the news out right up front,” the former chief said. “This is very difficult, but you have to be direct — and then you have to be very comforting.

“I learned so much from him.”

As one of his last official acts, Rodriguez emailed the chaplains and officers involved in De Guzman’s funeral. He expressed pride in the group, appreciation for their hard work and compassion.

Many of the same people are now preparing Rodriguez’s services. “They are pulling out all the stops to make this a nice celebration for him,” Zwibel said. “He was big in their life.”

Rodriguez is survived by his mother, Jennie Rodriguez; his siblings, Jennie Rodriguez, Gloria Taylor, Linda Rodriguez and Jess Rodriguez; and 10 nieces and nephews.

At the funeral, the family will be joined by many priests, rabbis and ministers; community organizers; and much of the San Diego Police Department. Zwibel will deliver one of the readings and act as a pallbearer.

“He was my godfather,” the sergeant said.

Basic information is provided as a courtesy and is obtained from a variety of sources including public data, museum files and or other mediums. While the San Diego Police Historical Association strives for accuracy, there can be issues beyond our control which renders us unable to attest to the veracity of what is presented. More specific information may be available if research is conducted. Research is done at a cost of $50 per hour with no assurances of the outcome. For additional info please contact us.