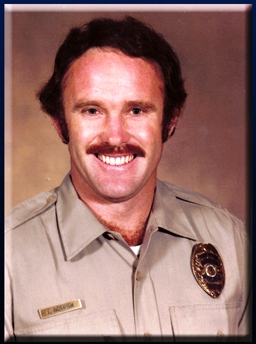

OFFICER LAURENCE M. INGRAHAM

ID 3020

SDPD 04/14/1980 - 10/19/1984

07/02/1950 - 05/08/2019

THE THIN BLUE LINE

Larry M. Ingraham, a highly-decorated police officer, criminal justice professor, and advocate for the rights of the developmentally disabled, died on May 8 of complications following a stroke. He was 68.

Larry devoted his life to protecting others, including three decades as a sworn peace officer patrolling the streets, investigating crimes, and securing the jails in and around San Diego.

After suffering multiple serious injuries in the line of duty, he began a second career training the next generation of law enforcement officers. Larry later channeled his experience into a successful legal battle that exposed the cover-up of his autistic brother's violent death in a state-run institution for the developmentally disabled, which led to statewide reforms.

He served as a beloved mentor to young people throughout his life. Larry was an Elder at Trinity Presbyterian Church. He volunteered countless hours to help students at Trinity Christian School, where he started a program that allowed eighth graders to guide younger students and help them with homework.

Above all, he was a loving husband, father, and devoted friend. He is survived by his wife, Julie, daughter, Morgan, and son, Joey, who miss him like crazy. "He had a gift of encouragement," Julie says. "He made people feel seen and valued. He had the ability to connect with the shyest child or the most dangerous inmate."

Laurence Mitchell Ingraham was born July 2, 1950 and grew up in La Mesa with four sisters (Diane, Yvonne, Virginia, and Jacqueline) and a brother, Van. His father, Richard Ingraham, was an executive at General Dynamics, and his mother, Jane Robert, managed the household and cared for their six children.

Larry was particularly protective of Van, his baby brother, whose developmental disabilities prevented him from forming words and caring for himself. He had a special relationship with his sister Jacqueline and spoke with her every day.

Larry joined the El Cajon Police Department in 1975 as an officer and finished his bachelor's degree in sociology at San Diego State University in 1977.

He transferred up to the San Diego Police Department in 1980, quickly attracting praise for his hustle and bravery.

Donovan Jacobs got to know Larry when they were young officers, as they ran into each other booking criminal suspects. Donovan said they were "20-80" officers, the 20% of the force that makes 80% of the arrests. They became fast, decades-long friends.

On June 6, 1981, a dispute in the Linda Vista neighborhood turned violent and the police were summoned. One of the combatants ambushed the first pair of officers on the scene, shooting them to death before retreating inside his home to continue firing on the neighborhood and police. Larry and fellow SWAT officer Gary Evans arrived under heavy gunfire shortly thereafter. They took position in a nearby house, Larry working as spotter, and took out the gunman with one shot.

SDPD awarded Larry a Medal of Valor for his "valorous actions ended a homicidal barrage that would have claimed more victims had it continued," the citation reads.

The following year, Larry received a commendation for a long list of impressive police work. His accomplishments included drug busts, solved burglaries, the recovery of "ten stolen Porsches," and an investigation that identified members of the Hell's Angels biker gang for the FBI.

Larry was wounded in an on-duty shooting and took a disability retirement in 1986. He spent four years as a counselor for the homeless and indigent, then returned to law enforcement as a deputy at the San Diego Sheriff's Department in 1990.

Larry worked in the county jails for 10 years, rising to the rank of sergeant. He suffered a broken neck in 2000 and his second on-duty injury ended his time as an active peace officer. Upon recovering, Larry founded a corrections academy at Grossmont College in El Cajon, teaching courses on justice administration, ethics, and leadership.

In 2002, he earned a master's degree in human behavior from National University. Larry went on to train and inspire more than a thousand law enforcement professionals. His final post was as a professor of criminal justice at Point Loma Nazarene University.

He was conservator for his brother Van, who lived for decades at Fairview Developmental Center, a state-run institution in Costa Mesa for the developmentally disabled.

On June 6, 2007, Van suffered a broken neck in his room and died days later. Fairview staff reported he had slipped out of bed. But a neurosurgeon treating Van took Larry aside and surmised: "Somebody did this to your brother. A short fall could not have caused so severe an injury.”

Van died six days later. Larry began investigating immediately. He partnered with his friend Donovan, who had become an attorney. They filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the California Department of Developmental Services and collected evidence of a Fairview nursing assistant's involvement in Van's death. They also exhaustively documented flaws in the investigation of Van's death by in-house police. The state settled the lawsuit.

In 2011, Larry and Donovan provided their work and records to a reporter at the Center for Investigative Reporting. Those records ignited a yearlong series of news stories exposing an array of abuse against disabled patients and cover-up.

In response, Gov. Jerry Brown signed two new laws to protect those living at developmental centers and the state moved to close most of the institutions. Larry's relentless effort and love helped thousands of people throughout California.

He brought a bursting energy to each day, whether solving crimes or playing flag football at his son's school, where the kids greeted him with chants of, "Larry! Larry! Larry!" He continued rousing people to action to the end.

In the days after his stroke, more than a hundred visitors streamed into Larry's hospital room to share stories of how they benefited by knowing him and to say goodbye. He is dearly missed.

Basic information is provided as a courtesy and is obtained from a variety of sources including public data, museum files and or other mediums. While the San Diego Police Historical Association strives for accuracy, there can be issues beyond our control which renders us unable to attest to the veracity of what is presented. More specific information may be available if research is conducted. Research is done at a cost of $50 per hour with no assurances of the outcome. For additional info please contact us.